Telegram recently hosted a contest

to backport Liquid Glass to earlier versions of iOS. Having just shipped the first version

of an

app I’d been working on, I had the opportunity to develop a solution.

The deadline was the day after Christmas, which made for a tight timeline, but overall

I’m quite happy with the result.

I’ll go over some of the more interesting parts of the implementation below, but you

can check out the full code on Github.

The Problem

The challenge was to create custom implementations of several UI elements that mimicked

the Liquid Glass effect of iOS 26, and worked all the way back to iOS 13. In addition to

aesthetic accuracy and appeal, submissions would be evaluated on performance, memory

consumption, and battery impact.

This last point presented a problem because, while the Liquid Glass effect can be

implemented as a Metal shader, there’s no supported way to apply a shader directly

to a UIView (outside of SwiftUI-only APIs introduced in iOS 17).

One possible workaround is to drive the effect using a CADisplayLink, where, on every

frame, we snapshot the view hierarchy and apply a shader to the resulting image. While

technically possible, though, this approach puts significant stress on the CPU and is far

less efficient than effects that integrate directly with Core Animation’s render

pass.

Because of this I decided not to use Metal shaders at all. This seemed to be the right

choice, but if other contestants got them to work efficiently, I’d be very curious

to know how they did it.

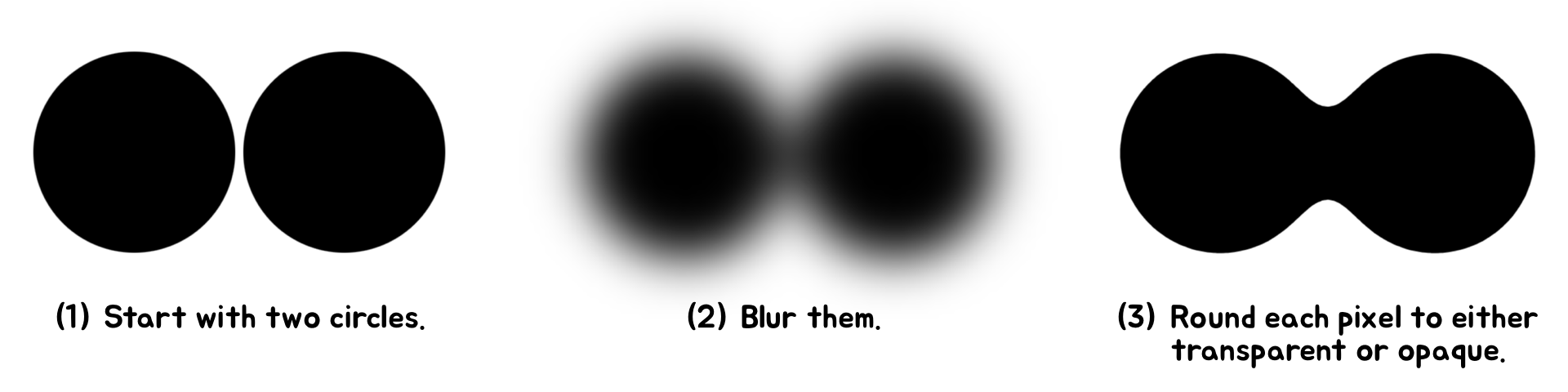

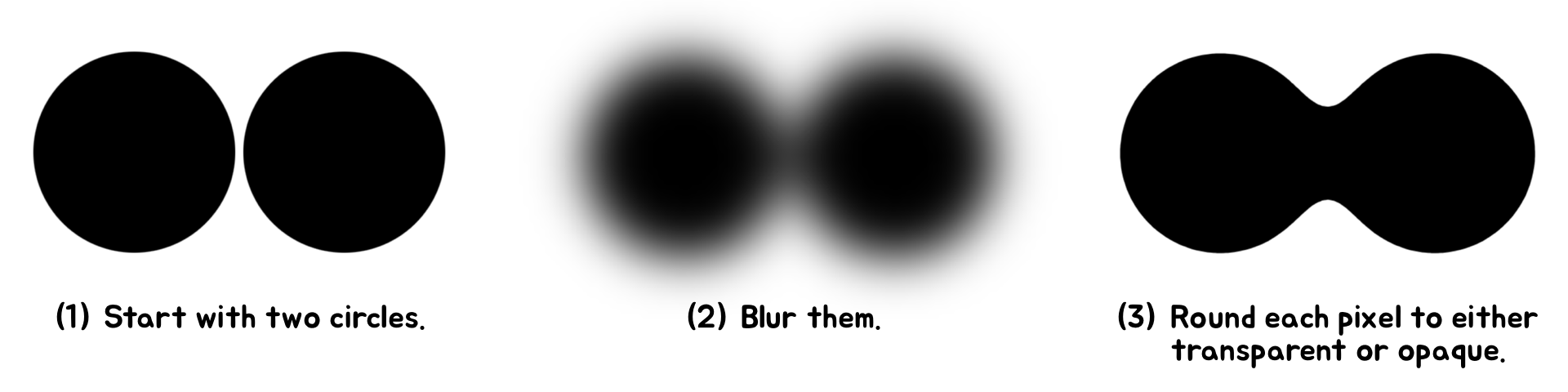

Taking Inspiration from Metaballs

I decided instead to approximate the Liquid Glass effect by taking inspiration from a

technique for making metaballs. While not as visually accurate as a shader-based approach, this method is far more

efficient, which I think is a worthy tradeoff given the constraints of the contest.

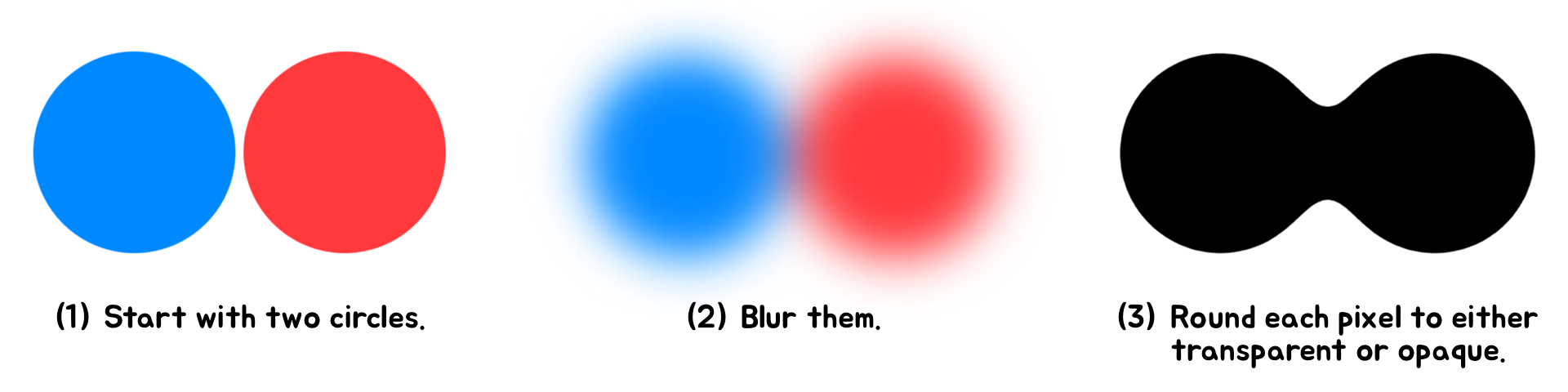

Here’s how it works:

In this simple example we see how the effect creates a smooth, liquid-like appearance, as

if the circles (or metaballs) were merging together. We’ll adapt this technique to

mimic the distortion effect of Liquid Glass, but first we must implement the technique

itself. For that we turn to the arcane magic of CAFilter.

CAFilter is a powerful but private API used for applying filters to Core Animation layers.

Every UIView is backed by a CALayer, so it works out of the box with UIKit. And unlike

custom shaders, CAFilters are applied directly to the render pipeline, making them very

efficient.

The only issue is that, because CAFilter is a private API, there’s no official

documentation on how to use it, making it a bit of a black box to work with. Officially,

private APIs are not allowed in apps submitted to the App Store. However, the contest

explicitly allows their use, and Telegram already uses them in other parts of the app, so

I considered it reasonable to incorporate them into my solution.

This Github repository provides a great starting point for seeing the types of CAFilters available.

If we look closely, two stand out as being particularly useful.

First is the Gaussian blur filter. This one is straightforward to understand, as it just

blurs the layer it’s applied to. It accepts a number of parameters, but the most

important is inputRadius, which controls the amount of blur. The blur filter is a commonly

used CAFilter and Telegram already has helper methods for creating it.

The second is the alpha threshold filter. This filter is much lesser known; in fact, I

haven’t even seen it mentioned anywhere before. It works by making pixels

transparent if their alpha value is below a certain threshold, or opaque if above it. A

parameter called inputAmount determines this threshold, and another called inputColor

determines the color when pixels are opaque.

Basically, the Gaussian blur softens the edges of the views, and the alpha threshold

sharpens them back up. And if we set the threshold to 0.5, nonoverlapping edges will be

identical to how they appeared before the filter was applied. This means a metaball on its

own appears as an unaffected circle.

All we have to do now is assign these filters to a container layer, configure their

properties, and all sublayers (and subviews) will be rendered with the effect. And because

this work is GPU-accelerated, it remains snappy and efficient when animated.

Making a UISwitch

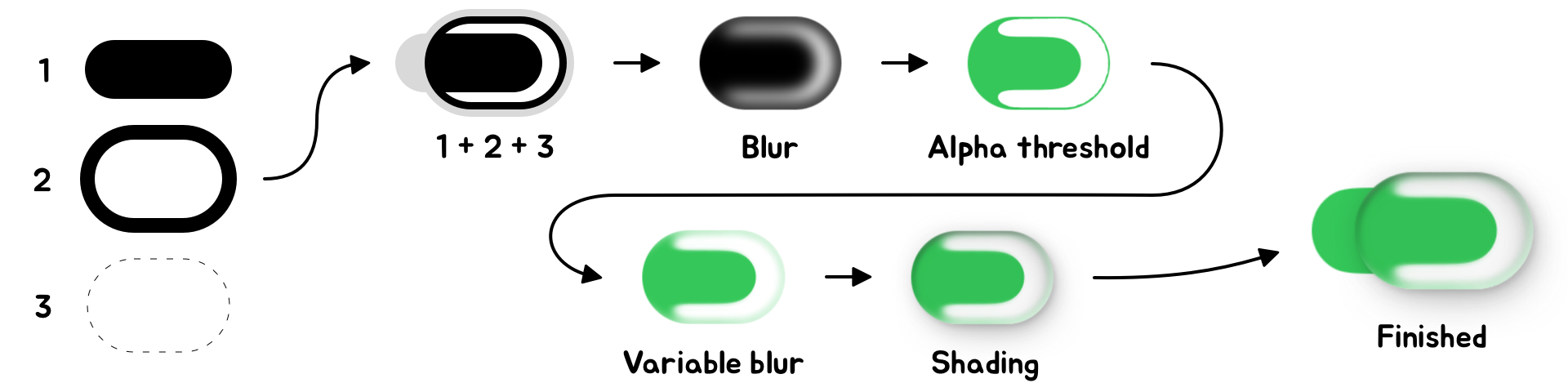

With the metaball effect in place, we can adapt it to UI elements. We’ll start with

a simple one: a UISwitch.

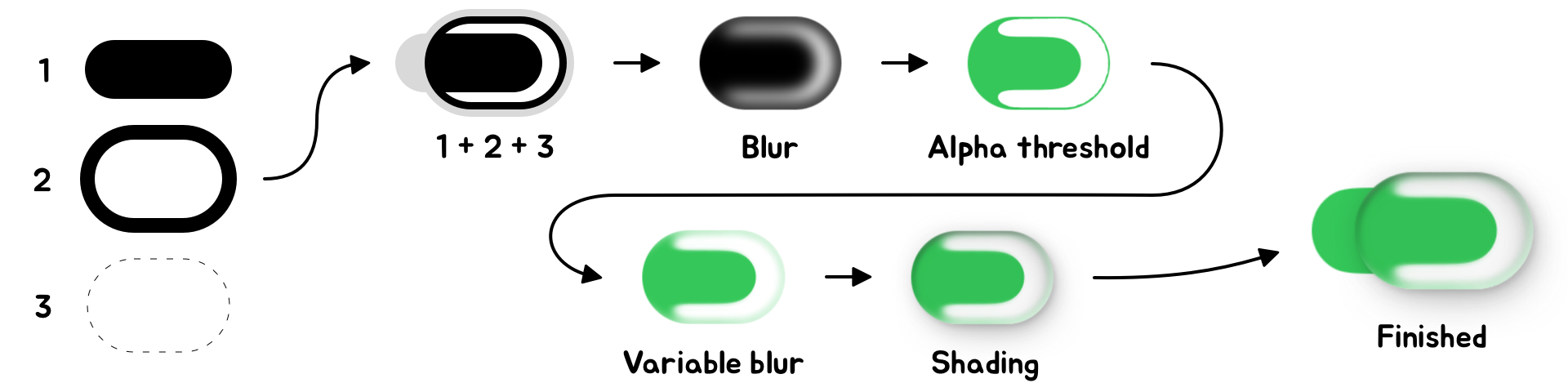

I’ll go over each step in detail, but I’ll start by showing an overview of the

whole process:

The first few steps should look familiar, but notice the shapes are now different. Instead

of two circles we use two pill shapes: one that’s filled in, and another

that’s just an outline. These are labeled 1 and 2 in the diagram, respectively.

These pill shapes are added to a container view, labeled 3, that clips its content into

yet another pill shape. We apply the blur and alpha threshold filters to this container

view.

The alpha threshold produces a shape with sharp edges, so in the next step we make them a

bit softer. To do this we add a third filter to the container view, called a variable

blur.

The variable blur is a lot like the blur we’re already familiar with. It accepts a

parameter called inputRadius that determines the amount of blur, but it also accepts a

parameter called inputMaskImage. The alpha channel of this image determines how much blur

to apply at each pixel: opaque pixels are fully blurred, and transparent pixels

aren’t blurred at all. For the switch, we apply a mask image that is black (blurred)

towards the edges and transparent (not blurred) towards the middle.

The next step is to add shading. This part is straightforward: all shadows and highlights

are baked into a single image and added as a UIImageView right on top of everything. The

image view is composited using a multiply blend mode.

Prerendering the shading has several advantages. We can add as many shadows as we want,

and there will be no performance cost over that of the image itself. Moreover, if we load

the image from an asset catalog, we can specify an alternative version that will be used

in dark mode. The downside is that we must know the size of the image in advance, but this

isn’t a problem: UISwitches have a fixed size.

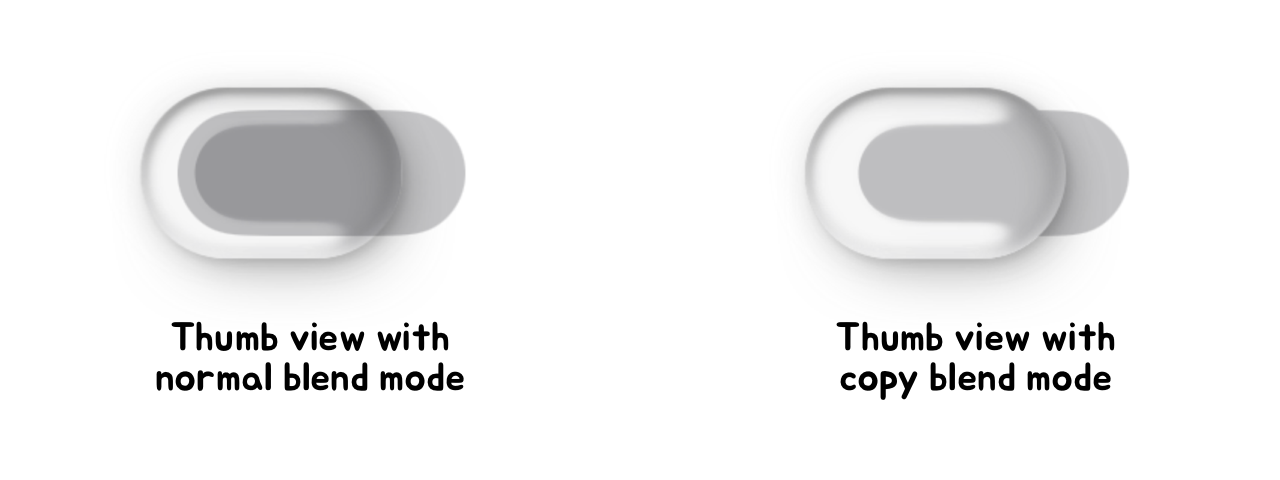

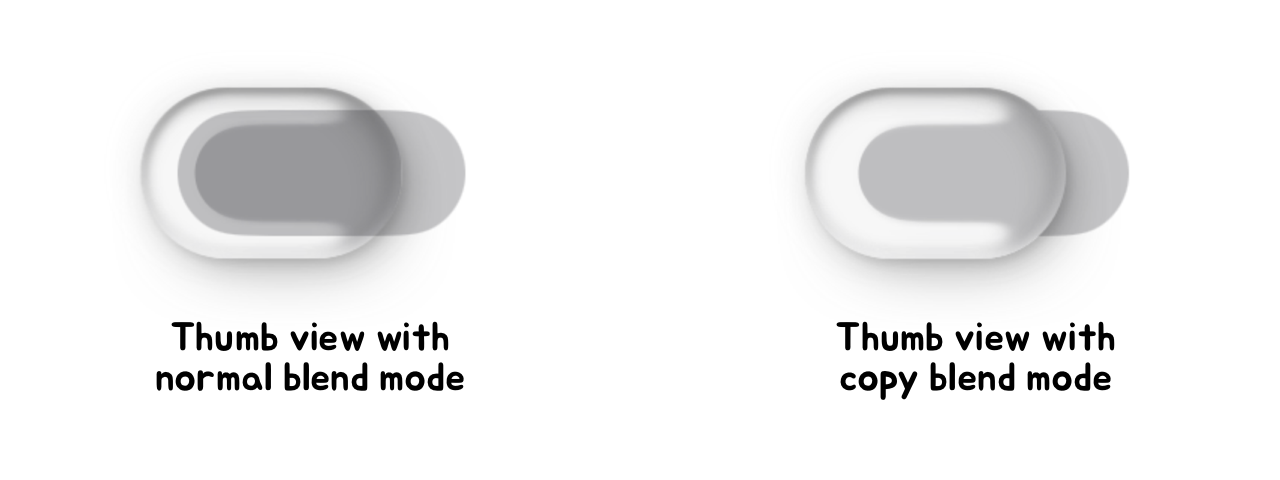

The last step is to add the track view. This is just a UIView with a background color

that’s added beneath the thumb view we just created. However, we want the thumb view

to erase the portion of the track it covers. To do this, we set the thumb view’s

blend mode to copy. This makes the thumb view completely replace the pixels it covers,

effectively cutting a hole in the track below it.

This completes the visual portion of the switch. This is only half the work in its

implementation; the other half is making it interactive. I’ll briefly outline that

process here, noting that the animations are all driven by a CADisplayLink as opposed to

CAAnimations.

Telegram uses CAAnimations in many other parts of the app, but I don’t think

they’re the best tool for this specific problem. CAAnimations work best as

“fire and forget” animations. Rather, our switch must be interactive and

interruptible, with state that’s a function of multiple concurrently running timing

curves.

To fully model the motion of the switch I used four independently running spring

simulations. Each one was updated each frame according to the closed-form analytical

solution of a damped harmonic oscillator. I chose to advance the simulations using a fixed

timestep as opposed to the variable delta between frames; this makes the animation pause

as opposed to skipping ahead in the event of a dropped frame. I find this behavior less

visually jarring.

The first spring drives the horizontal position of the thumb view. When the switch is

dragged, we update the target of this spring—not the position itself—and let

it continue to animate towards its target. This gives the thumb a nice, liquidy feel that

seems to “chase” the user’s finger. It also damps its velocity, which

will be important later. When the user finishes dragging, we set the target to the on or

off position and let it animate to completion.

The second spring drives the scale of the thumb view. We scale up the thumb when the

switch begins tracking a touch, and scale it back down when the touch finishes. We also

use a timer to enforce a minimum duration from when the thumb scales up to when it scales

back down. This ensures the thumb still animates in the event of a very quick tap on the

switch.

The third spring drives the jiggle of the thumb view. We stretch the thumb horizontally in

proportion to the spring’s value, and vertically in proportion to its inverse. This

gives the thumb a nice, bouncy feel as it moves. The target of this spring is updated each

frame according to the velocity of the first spring, meaning the faster it’s

dragged, the more it jiggles. Note that, because of this dependency, special care must be

taken to ensure the springs are updated in the correct order.

The final spring drives the color of the track. Rather than interpolating the RGB values,

we composite the on color over the off color for an interpolated alpha value. This

produces more accurate in-between colors when the off color is semitransparent. Updating

the color requires updating the inputColor of the alpha threshold filter. This is another

advantage of animating with a CADisplayLink: animating properties of CAFilters can be

unreliable with CAAnimations.

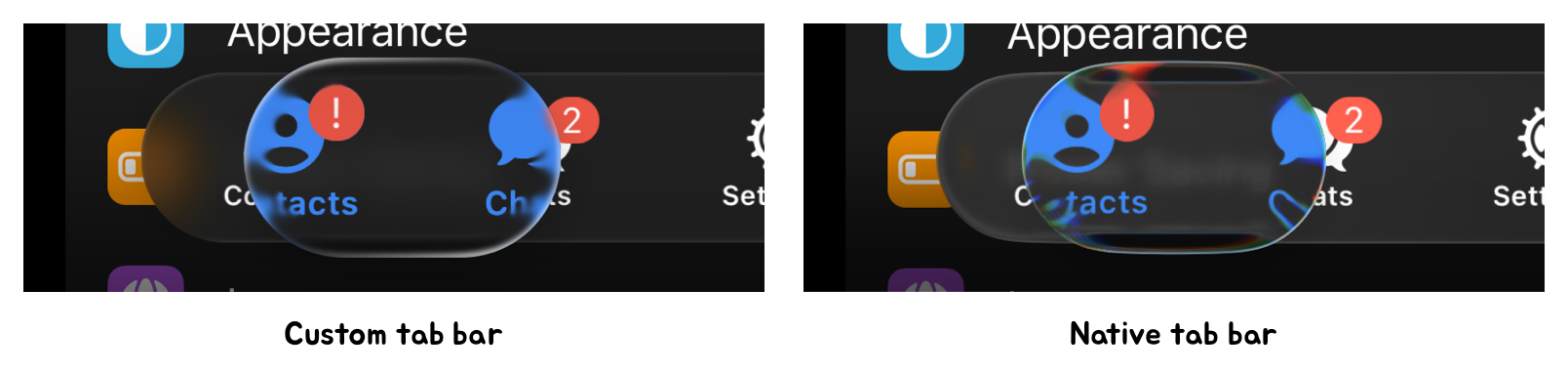

Making a UISlider & UITabBar

The Telegram contest also called for a custom UISlider and UITabBar. I made these using a

process very similar to that of the switch, so I’ll only comment on a few points of

interest.

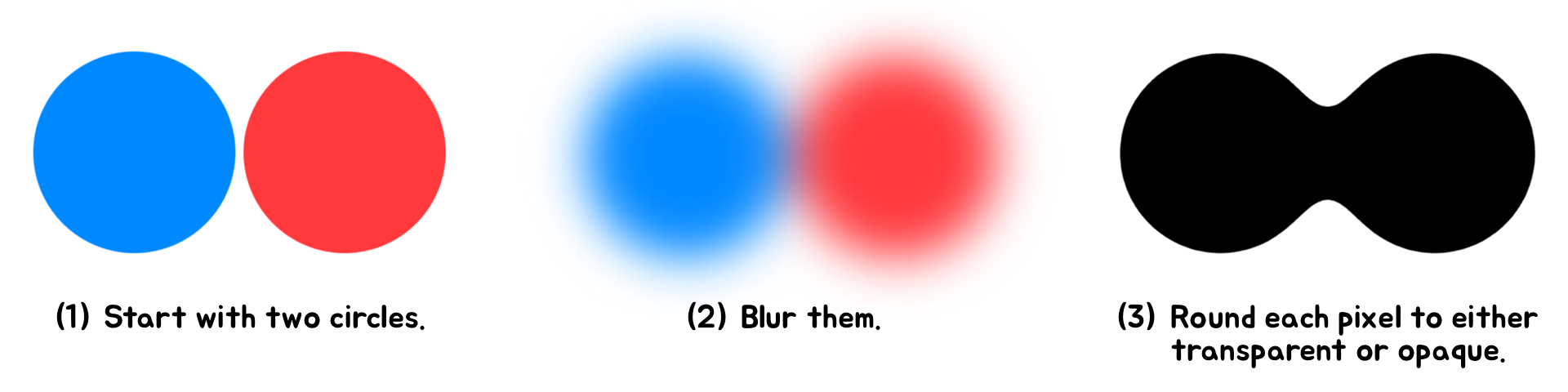

First off, up until this point, I haven’t emphasized an important detail of the

alpha threshold filter: it doesn’t preserve colors.

Let’s revisit the metaball example to see what I mean:

This isn’t an issue when the view contains only one color; we just set the

inputColor to the original color of the view. But for the UISlider, there are two colors

we need to consider: one for the track’s background, and another for the part

that’s filled in.

To solve this, we basically do the metaball effect twice—once for each

color—then layer the effects on top of each other. I found this to be an effective

approach, but it highlights a weakness of this technique for approximating Liquid Glass:

it doesn’t scale well for views with multiple colors.

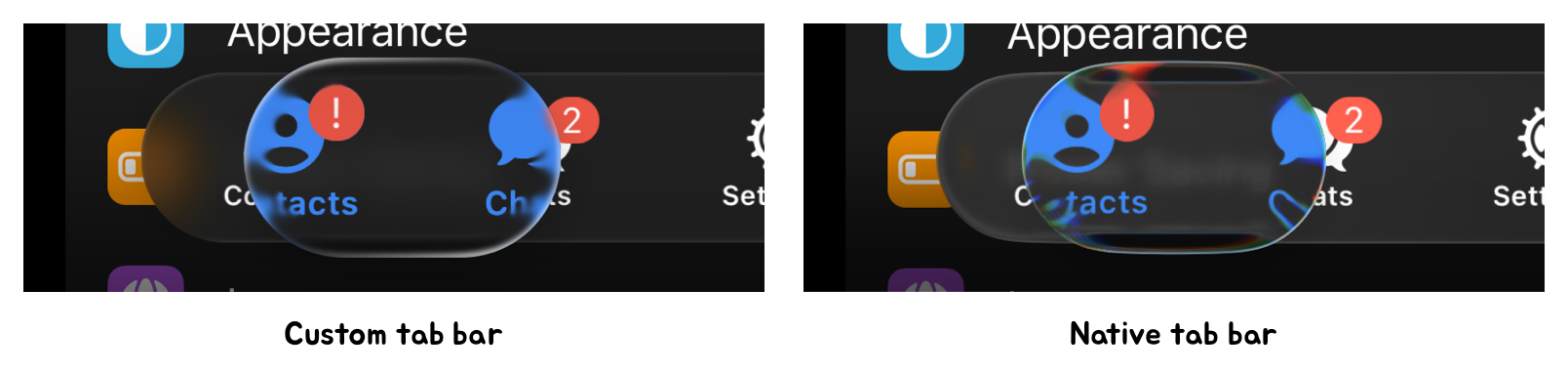

We encounter this problem again with the tab bar, which can contain up to three colors:

one for the symbols and text, and another two for the badge that can appear in the corner.

In this case I solved the problem a different way. We only apply the metaball effect for

the color of the symbols and text. Then, on top of that, we add the views again, but

without any filters. This brings back the original colors and sharpness. Finally, we apply

our variable blur and shading to the entire hierarchy.

In none of our examples have the limitations of the metaball technique been a dealbreaker.

We control the layers the effect is applied to, letting us make strong assumptions about

their content and colors. This wouldn’t be possible if we applied the effect to an

arbitrary background view, for example. In this case we would need a different approach.

Overall, I think this is a powerful technique for approximating Liquid Glass. While not

accurate to the pixel, it is visually convincing, maintainable, and efficient enough to

run smoothly on older devices. This efficiency, coupled with a spring-based animation

system using CADisplayLink, allows us to replicate the fluid interactivity of Liquid

Glass, which contributes greatly to its overall feel.